Preface

Gimme a minute; really quickly, I want to give you some background on the way we at Atlan fixed our testing troubles.

A feature that we were working on happened to be un-testable with

unit tests and E2E test suites; we were developing a Directed Graph (Digraph)

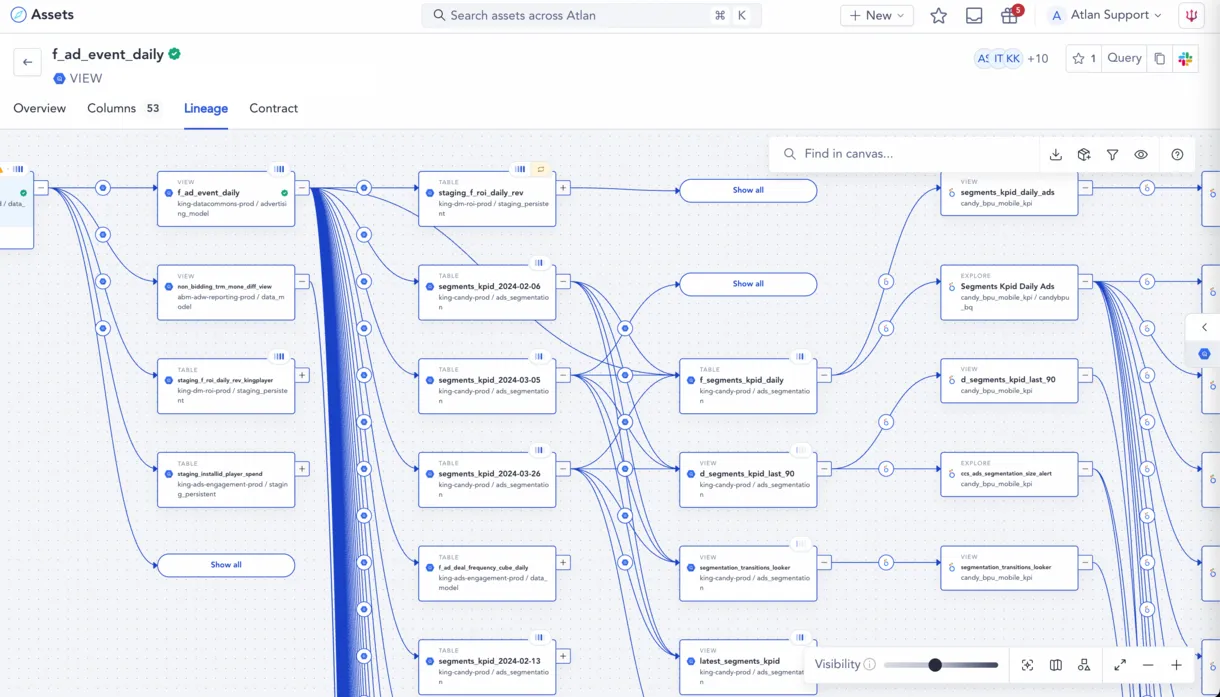

renderer on the front-end that paints nodes and edges into an HTML <canvas> element. It looked

something like this:

Data Lineage - The digraph renderer

Since we were rendering into the canvas, it was difficult to test

our feature due to <canvas>’s lack of DOM representation.

Screenshot comparison or pixel-based verification is difficult,

and so is simulating click events because that needs coordinate-based positioning.

…so, we ran the tests on our code itself.

We threw the tests into the code that we wrote, as opposed to running CI workflows for unit or E2E tests. This also means that the tests run during the app’s run-time.

The outcomes were:

- We were able to test if what we rendered onto the canvas was actually correct.

- Make sure that the data we are fetching from the back-end is of the correct form.

- The state of the front-end app is correct and is never something we don’t expect.

- The assumptions that we make about our code and it’s state are correct.

We essentially defined a set of “allowed behaviours” that the app should operate in. And any time the app does something that we don’t expect, we know exactly what to fix. We defined the “happy path” and made sure we know when the app diverges from it.

…But how did we do that?

Enter: Assertions

When we write code, we tend to make reasonable assumptions about the code and the environment we are writing the code in.

These assumptions could be about the state of your system, the data within the system and how it is passed around, what functions expect as input and are expected to output, their interfacing, and so on.

Sometimes, these assumptions are wrong and this results in developer errors. Hell, sometimes even when you are aware about your environment, the code you write is still very prone to developer errors.

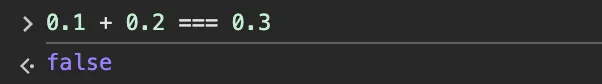

Like this well-known behaviour in JavaScript:

To no fault of the developer, they would incorrectly assume 0.1 + 0.2 to be 0.3.

Because why would anyone ever assume otherwise?

Assertions are a way to enforce correctness into your code such that your code itself screams at you when it is doing something you didn’t expect it to.

This also requires a slight mindset shift in how you approach testing:

- With unit tests, you predict and account for edge cases and make sure they are handled properly.

- With assertions, you define the happy path of the software directly, and anytime the code diverges from it, it will automatically complain.

This is not to compare unit tests and assertions, but a neat consequence of writing tests that run along your code to keep in mind!

We’ll move on to much more powerful examples of assertions, but let’s start with

some really simple assertions just using console.assert, before we get to the heart of it:

type Foo = {

bar?: any // Peak production TypeScript code

}

const factorialFoo = (foo: Foo) => {

console.assert(Number.isInteger(foo.bar), "bar must exist and must be an integer")

console.assert(foo.bar > 0, "bar must be positive")

// We now proceed with the confidence that our assumptions are true

return factorial(foo.bar)

}

// Every time you use the function in an unintended way, the assertion fails.

factorialFoo({ bar: '5.2' }) // Assertion failed: bar must exist and must be an integer

factorialFoo({}) // Assertion failed: bar must exist and must be an integer

factorialFoo({ bar: -5 }) // Assertion failed: bar must be positive

// But with valid input, it works just as expected:

factorialFoo({ bar: 5 }) // 120

So what just happened here?

We wrote two assertions within our function definition that state exactly what conditions must be true for our function to work as expected:

"bar must exist and must be an integer" and "bar must be positive or 0".

Any time these assumptions are false, console.assert will tell you that the assertion is failing.

We have essentially programmed in an invariance; that Foo.bar should always be a number.

Instead of making safeguards for all that foo.bar could be, we asserted exactly what it should be.

But this isn’t yet using assertions to their full capacity.

Levelling up our asserts

So far in this blog I’ve shown you just a basic use case of assertions with console.assert, but that’s just the

building block of an assert() implementation you would actually use.

This assert implementation has the following features:

- Control when the assertions run:

- If the

env.MODEisdevelopment, enable all the assertions. - If the

env.MODEisproduction, enable only the assertions intended to run in production. - If the

env.MODEisnoAssert, disable all the assertions.

- If the

- Tracking when an assertion fails and logging it with the program’s state for Sentry-like error monitoring.

- Ability to debug the program’s seed state that lead to an assertion failing.

- Ability to throw an error and crash the program if a failing assertion might lead to a critical bug.

Here’s a simple factory function (createAssert) in just ~50 lines of code that produces assertion functions:

const env = import.meta.env.MODE

const trackEvent = (eventName: string, data: any) => {

// Send event to Sentry or other monitoring services

}

type AssertFunction = (assertion: string, condition: boolean, programState?: any) => void

interface AssertOptions {

trackInProd?: boolean

throwOnFail?: boolean

}

// Factory function to create assertion functions

const createAssert = (options: AssertOptions = {}): AssertFunction => {

const { trackInProd = false, throwOnFail = false } = options

if (env === 'noAssert') {

return () => {}

}

if (env === 'development') {

return (assertion: string, condition: boolean, programState?: any) => {

if (!condition) {

console.error(`Assertion Failed: ${assertion}`)

console.error('Program state:', programState ?? {})

if (throwOnFail) {

const error = new Error(`Assertion failed: ${assertion}`)

throw error

}

}

};

}

if (env === 'production' && trackInProd) {

return (assertion: string, condition: boolean, programState?: any) => {

if (!condition) {

trackEvent(

`assertion_failed_${assertion}`,

{ programState: programState ?? {} }

);

if (throwOnFail) {

const error = new Error(`Assertion failed: ${assertion}`);

throw error

}

}

}

}

// Default for other envs

return () => {}

};

With the factory function implemented, this is how you create the assert functions:

// Runs only in dev mode, disabled in prod:

const assert = createAssert()

// Runs only in dev mode, and throws when it fails:

const criticalAssert = createAssert({ throwOnFail: true })

// Tracks failures in prod and logs it to Sentry/Mixpanel

const prodAssert = createAssert({ trackInProd: true })

// Tracks failures in prod and throws

const criticalProdAssert = createAssert({ throwOnFail: true, trackInProd: true })

And this is how you use them for actual code:

// In a funds transfer service

async function transferFunds(sourceAccountId, destinationAccountId, amount, userId) {

// Validate inputs

criticalProdAssert(

"source_account_exists",

typeof sourceAccountId === 'string' && sourceAccountId.length > 0,

{ sourceAccountId }

);

criticalProdAssert(

"destination_account_exists",

typeof destinationAccountId === 'string' && destinationAccountId.length > 0,

{ destinationAccountId }

);

criticalProdAssert(

"amount_valid",

typeof amount === 'number' && amount > 0 && isFinite(amount),

{ amount }

);

// All is good so far, load the accounts!:

const sourceAccount = await accountService.getAccount(sourceAccountId);

const destinationAccount = await accountService.getAccount(destinationAccountId);

criticalProdAssert(

"source_account_found",

sourceAccount !== null,

{ sourceAccountId, userId }

);

criticalProdAssert(

"destination_account_found",

destinationAccount !== null,

{ destinationAccountId, userId }

);

criticalProdAssert(

"source_account_belongs_to_user",

sourceAccount.ownerId === userId,

{

sourceAccountId,

sourceAccountOwnerId: sourceAccount.ownerId,

requestingUserId: userId

}

);

criticalProdAssert(

"sufficient_funds",

sourceAccount.balance >= amount,

{

sourceAccountId,

currentBalance: sourceAccount.balance,

requestedAmount: amount,

}

);

// All assertions pass! We are safe to proceed:

const transaction = await db.beginTransaction();

try {

await accountService.debitAccount(sourceAccountId, amount, transaction);

await accountService.creditAccount(destinationAccountId, amount, transaction);

const updatedSourceAccount = await accountService.getAccount(sourceAccountId, transaction);

criticalProdAssert(

"debit_applied_correctly",

Math.abs(sourceAccount.balance - updatedSourceAccount.balance - amount) < 0.001,

{

sourceAccountId,

originalBalance: sourceAccount.balance,

newBalance: updatedSourceAccount.balance,

amount,

difference: sourceAccount.balance - updatedSourceAccount.balance

}

);

// All is good, commit the transaction!

await transaction.commit();

return {

success: true,

transactionId: transaction.id,

newSourceBalance: updatedSourceAccount.balance

};

} catch (error) {

await transaction.rollback();

throw error;

}

}

Every assertion you apply here enforces what the environment needs to be invariant so you can move forward with the confidence that your assumptions are correct.

I’m done; be safe, and write safe code! Cheers 🥂

Further reading:

-

TigerBeetle’s safety guide 🔗 has a neat set of rules on using asserts for even better safety. Here are the most important bits:

-

Assert all function arguments and return values, pre/postconditions and invariants. A function must not operate blindly on data it has not checked. The purpose of a function is to increase the probability that a program is correct. Assertions within a function are part of how functions serve this purpose. The assertion density of the code must average a minimum of two assertions per function.

-

Pair assertions 🔗. For every property you want to enforce, try to find at least two different code paths where an assertion can be added. For example, assert validity of data right before writing it to disk, and also immediately after reading from disk.

-

The golden rule of assertions is to assert the positive space that you do expect AND to assert the negative space that you do not expect because where data moves across the valid/invalid boundary between these spaces is where interesting bugs are often found. This is also why tests must test exhaustively, not only with valid data but also with invalid data, and as valid data becomes invalid.

-